.Some days ago, Lars, Gjermund and I went to the Negev desert in order to learn more about the situation for the Bedouins who are living there. On our way, we crossed the checkpoint between Bethlehem and Jerusalem. It was very crowded this day. It took us one hour just to get through the first lane leading into the terminal itself. As we were waiting, we met Gunnar, who is here with

EAPPI, the accompaniment program of the World Council of Churches. I asked him what was going on, and he said: "Well, there are two girls sitting there, and one is just chewing gum and talking on the phone. I tell you, this has been the worst month since I got here." After a while a friend called the humanitarian number of the Israeli military. They told us to wait. Nothing happened.

In the lane at the checkpoint.

In Beer Sheva we met Abu Ali al-Sbeih from The Regional Council for the Unrecognized Villages in the Negev (

RCUV). "I wanted you to come, to see how people live in a democracy", he said. Most of the Bedouins in the Negev fled to the West Bank, Gaza and Sinai during the Arab-Israeli war in 1948. Those who remained were forced to move to the northern parts of the Negev, around the city of Beer Sheva. By the end of the 1950s, the Israeli state had managed to appropriate over 90 percent of all land in the Negev. In the 60s and 70s, the government planned seven townships where they wanted to "concentrate" the Bedouin population, without consulting them. Those who refuse to move to these townships, live in the so-called

unrecognized villages.

While 134 agricultural communities have been developed for the exclusive use of the Jewish population of the Negev, not a single Arab community has been authorized since 1948. Consequently, you will not find the unrecognized villages in the Negev on a map, and they do not receive services or infrastrucure like water, electricity or roads. To construct permanent buildings is illegal, so Israeli authorities regularly destroy Bedouin homes. Even villages and houses that were there long before the state of Israel was established, suddenly have become illegal.

"There are 45 villages with 90,000 inhabitants", Abu Ali al-Sbeih tells us.

"They destroy our houses and take our land to make us move to densely populated areas. We want to live as Bedouins, with animals and an agriculture with low water consumption, but that's impossible when we are placed in cities. Every week they come and destroy houses, because they say that they are illegal. But we have no one to apply to for permission."

He keeps describing how difficult the situation is. Children have to travel long ways to go to school. Many don't go. If a mother needs to take her child to the clinic, she will often have to walk several kilometers before she reaches a road. The schools -there are separate schools for Jews and Bedouins- have a bad quality. And all the time they see how different their situation is from that of Israeli Jews, who have everything they need.

Al-Sbeih takes us to two unrecognized villages. One of them is called Assir. The houses have been standing here for a long time. Then Israel built a high voltage wire just over the village. Now the inhabitants live with the risk of cancer.

"Every time there's a storm, the people here are so afraid that parts of the construction will fall down," al-Sbeih comments.

Assir.

In the other village, Khashm Zanna, 600 children are picked up by 12 buses every day to go to school.

"It costs more to drive these children back and forth than to have a school here. Why do they do it? Because they don't want us to live here".

Al-Sbeih tells us about the Regional Council, which represents the unrecognized villages to the state and the international society. They also arrange courses, where people learn to communicate about their own situation.

Sitting down for tea in Khashem Zana.

Abu Ali Al-Sbeih describes the beauty of the traditional Bedouin life: the music, the fellowship, the handicrafts and the love for the desert.

"Every type of nature has its special characteristics. The life of the Bedouins is tied to what is natural in the desert. We know how to live in harmony with it. And we appreciate it, the silence, for instance. I don't mind young people moving to the city. But those who want to live in the desert, are not allowed."

We ask Al-Sbeih how the Israeli government defends it policies towards the Bedouins.

"They listen to us, and they know what is going on, but they don't want to do as we say, because they want our land. They want to pressure and pressure and pressure us, so that we move.", he answers.

"When I open my door and go out, I meet limitations and barriers. I want a free life. I want to live in a world that stretches out, like the desert."

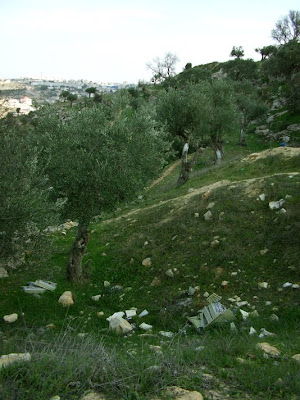

From Assir.

.